Cryptanalysis of intercepted Israeli drone feeds

Several days ago The Intercept published a story about how British and American intelligence (in the form of GCHQ and the NSA) tapped into live video feeds from Israeli drones and fighter jets as part of a program codenamed ‘Anarchist’. Footage was intercepted by RAF Troodos on Cyprus, a signal station run by Golf Section, Joint Service Signal Unit (JSSU). The article mentions how analysts first collected encrypted video signals at Troodos in 1998 and how signals were picked up from a variety of drones and fighter jets used by a variety of actors in the region, some of which were apparently sent in the clear and others which were encrypted. The supposed aim of the intercepted snapshorts seemed to be identification of which signals belonged with which aircraft, weapons system or radar and to demonstrate the capability was there.

Apart from the, admittedly unsurprising, fact that many of the sensitive signals floating around are sent in the clear what was particularly interesting in the piece is its mention of the use of publicly available open-source tools used for the decryption of those signals that were encrypted. This post intends to delve a little deeper into the technical details that emerge from the story and accompanying leaked documents.

Drone comms

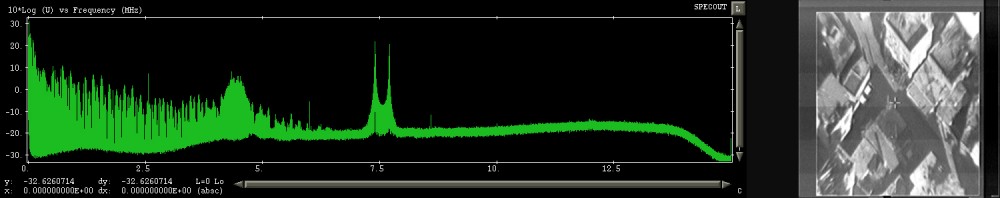

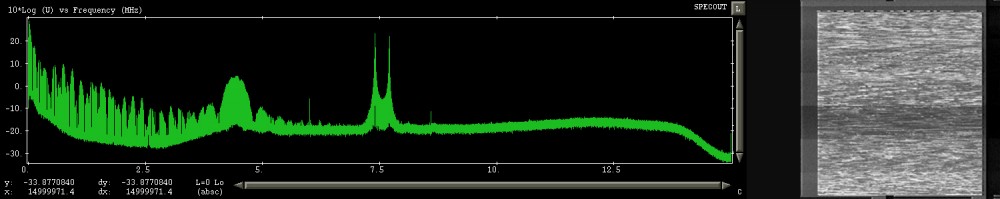

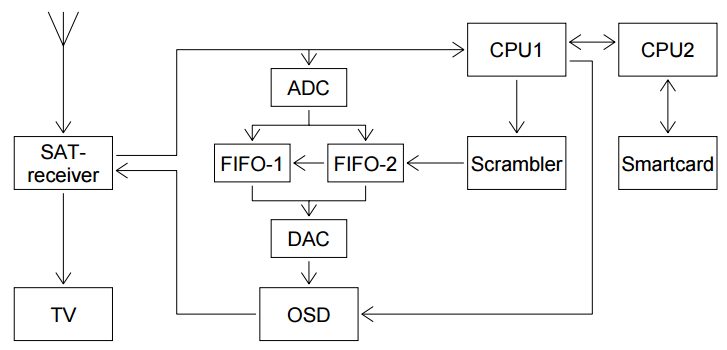

Drones often (but not always) communicate with ground controllers via satellite with this connect-back transmission known as the “downlink”. The Troodos antennas intercepted that downlink data by finding the right frequency for each drone. This accompanying leaked document gives an idea of what that looks like and mentions a ‘Signal of Interest’ (SOI) dubbed S455N emanating from an Israeli UAV and spotted at various moments in time. The signal employed Frequency-Shift Keying (FSK) modulation and was coded at 9.11MBauds occupying approximately 10MHz bandwidth. Subsequent signals processing revealed a payload with packets containing IP/UDP data carrying multiple protocols, the main protocol being Real-Time Transport Protocol (RTP) used for delivering audio and video content. The data contained in the RTP stream was a multi-stream MPEG 4 video with each stream corresponding to a different camera.

As the article from The Intercept mentions, however, drone feeds are vulnerable to interception not just from western intelligence agencies but from virtually anybody with the right (often cheap) commercially available equipment as U.S. forces in Iraq found out the hard way when they discovered a local insurgent group had used the SkyGrabber software (used to grab satallite internet data) to intercept unencrypted MQ-1 Predator drone video feeds. Here the drone sent its videofeed in encrypted form to the satellite but the satellite subsequently beamed it down to ground controllers in unencrypted form. Israel too found out about the dangers of unencrypted videofeeds the hard way when in 1997 Hezbollah operatives killed 12 Israeli commandos in an ambush in Lebanon after Hezbollah apparently intercepted unencrypted video footage from a drone accompanying the Israeli force. As a result Israel expanded its drone feed encryption efforts. A leaked training document for the ‘Anarchist’ program mentions how interception of scrambled analogue vidoe signals dates back to 1998, a year after the Ansariya ambush.

Drone signals encryption

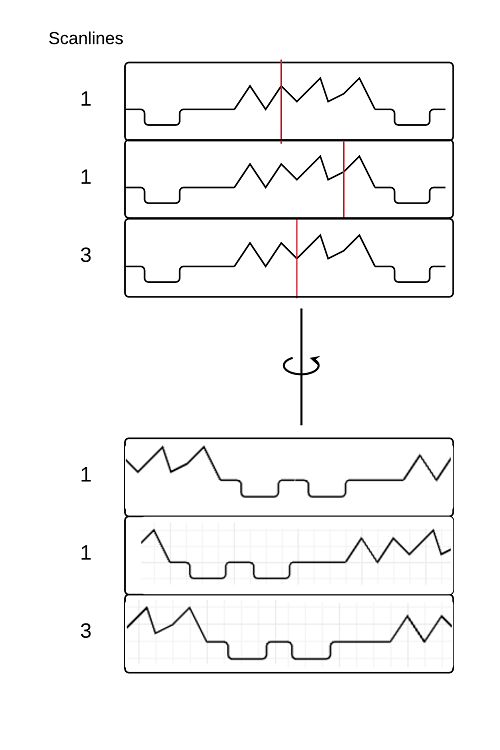

A SOI dubbed S455e described in the leaked training document is shown in both encrypted and decrypted form and it is noted that these are virtually indistinguishable when examined in the frequency domain, apart from an increase in energy at lower frequencies corresponding to image smoothening by the ‘scrambling’ (aka television encryption) process. The manual states that in the scrambled signal the video frame is unchanged and there are two lines of digital information encoded in the ‘teletext area’ at the top of the screen holding cryptographic metadata which revealed the scrambling technique is ‘line cut and rotate’ (dubbed ‘cut & slide’ in the GCHQ document). This technique, which consists of cutting each line of the video feed at a certain location and transmitting the two halves in opposite order, was used by the VideoCrypt cryptographic scheme originally introduced in 1989 by News Datacom (and used by SkyTV and other broadcasters) for smartcard-based analogue PayTV solutions before the switch to digital was made.

The manual mentions the availability of plenty of open source material discussing and implementing publicly known attacks on VideoCrypt, singling out Markus Kuhn’s AntiSky program in particular. The approach outlined in the GCHQ training manual is as follows:

- Intercept the SOI

- Capture a video frame in bitmap (BMP) from the processed SOI

- Use ImageMagick to convert the bitmap to portable pixmap (PPM)

- Use AntiSky to ‘descramble’ the image

- Use ImageMagick to view the clear image and convert it to a more convenient format if required

It is noted in the manual that the computing power needed to descramble images in near real time is considerable without use of dedicated hardware such as a video capture card for recording uncompressed images but that descrambling individual frames to determine image content is still very feasible.

VideoCrypt

So let’s take a look at the VideoCrypt scheme. VideoCrypt operates on analogue videofeeds using the Phase Alternating Line (PAL) encoding format. PAL video information is stored in lines from top to bottom in interlaced fashion. Each of the lines that make up a video frame is cut at one of 256 possible ‘cut points’ and the resulting two halves of each line are swapped around for transmission. The series of cutpoints (effectively the secret keystream) is determined by a pseudo-random sequence generated by a PRNG stored on a smart card (known as a ‘Viewing Card’).

In order to decode a signal the decoder would interface with the smart card to check if the card was authorised for a specific channel and if this was the case the decoder would seed the card’s PRNG with a seed transmitted with the video signal (as part of the earlier mentioned cryptographic metadata in the ‘teletext area’) to reproduce the correct sequence of cut points in order to unscramble the image.

Obviously the ‘line cut and rotate’ approach is rather meagre as permutations go since it only permutates the image at one point along one axis (the x-axis). A variant used by the BBC, called VideoCrypt-S, included ‘line shuffle scrambling’ which would permutate the image along the y-axis by shuffeling the order in which lines are transmitted (eg. line 5 may transmitted as line 10) using 6 blocks of 47 lines per field and supported three format (shuffeling either 282 lines, every alternate field or pseudo-randomly delaying the start position of the video in each line). It appears, however, that this variant was only in use by the BBC Select Service and in any case did not apply to the algorithm used to scramble the drone footage discussed in the documents released with the article.

The VideoCrypt PRNG and Keyed Hash Function

The 60-bit PRNG seed used for a given frame is derived from a 32-byte message (using a keyed hash function) and is fed into the PRNG (about which no details are known to be reported) which produces a sequence of 8-bit secret cut points, effectively constituting the keystream. The keyed hash function used by VideoCrypt was a custom hash function which also integrated a ‘signature check’ on the 32-byte message from which the seed is derived to complicate any encryption-oracle style attacks. The hash function, as outlined in Kuhn’s slides, looks as follows in Python (with the unpublished secret key based S-Box replaced with the identity mapping):

#!/usr/bin/env python

"""

VideoCrypt Keyed Hash Algorithm as described in http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~mgk25/vc-slides.pdf

"""

class VideoCryptHash:

def __init__(self):

# PRNG sequence

self.answ = [0]*8

self.j = 0

# Secret-key based S-Box (details unpublished so replaced with identity mapping)

self.sbox = [i for i in xrange(0x00, 0x100)]

return

# Round function as per BSkyB P07 card

def round_function(self, p):

self.answ[self.j] = (self.answ[self.j] ^ p)

c = self.sbox[self.answ[self.j] / 16] + self.sbox[(self.answ[self.j] % 16) + 16]

c = ((((~c) << 1) + p) >> 3) % 0x100

self.j = (self.j + 1) % 8

self.answ[self.j] = (self.answ[self.j] ^ c)

return

# Keyed hash function with 'signature check'

def keyed_hash(self, msg):

assert(len(msg) == 32)

self.answ = [0]*8

self.j = 0

for i in xrange(0, 27):

self.round_function(msg[i])

b = 0

for i in xrange(27, 31):

self.round_function(b)

self.round_function(b)

if (self.answ[self.j] != msg[i]):

return []

self.j = (self.j + 1) % 8 # Only in P07

b = msg[i]

for i in xrange(1, 65):

self.round_function(msg[31])

return self.answ

v = VideoCryptHash()

print v.keyed_hash([0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0x03,0xF6,0xED,0])

The keyed hash function was designed to withstand reproduction (ie. secret key recovery) by an attacker collecting many message/seed pairs, there seems to be no public documentation of how well it holds up against cryptanalysis. It is noted that in the original VideoCrypt system there is no card or decoder-specific information involved in the scheme and as such any one card can be used for several decoders (ie. a ‘card sharing attack’). Whether this would apply to the UAV ground controllers and the feeds of individual drones depends on how heavily modified the smart card part of the VideoCrypt implementation used in their feed security systems was.

Analysis of the VideoCrypt scrambling scheme

A passive attacker intercepting scrambled video feeds has the following pieces of information to work with:

- Cryptographic metadata: ie. the 32-byte message from which the PRNG seed is derived using a keyed hash function

- The video feed ‘ciphertext’

Given that we know nothing about the PRNG and don’t have access to the keyed hash function (either via its key or as some sort of oracle) the most direct approach here is a ciphertext-only analysis of the scrambled video feed. Luckily for an attacker, the scrambling permutation is rather uninvoled and can be broken without any need for the secret cutpoint keystream. Given that two consecutive lines in most images are almost identical one can exhaustively try all 256 possible cut points and select the best candidate which causes two adjacent lines to correlate optimally. Markus Kuhn’s AntiSky program used by GCHQ is an example of such a ‘brute force image processing’ attack (utilizing techniques from signals processing such as Fast Fourier Transform) which, while it might not work (or work equally well) for every image, seems to be effective enough in practice despite image quality loss. While the latter might have made the attack less attractive for PayTV pirates, intelligence analysts intercepting drone feeds wouldn’t be too concerned with the image being not crystal clear as long as valuable IMINT can be extracted.

A naive exhaustive search would require correlation of 256^n lines of w*n pixels each (where n is the number of lines). AntiSky, however, takes a more optimized approach which measures correlation of two lines at a particular offset as the sum of the products of pixels in the same column and uses a dynamic programming algorithm to reduce overall complexity. An improved version of the AntiSky algorithm is outlined by Michael Niedermayer (of FFmpeg fame) here as follows:

- (optional) downsampling to speed up cross-correlation

- Cross-Correlation: While AntiSky uses a FFT-based cross correlation, adaptive cross correlation would be preferable

- Mismatched line detection: Lines which can’t be properly matched using cross-correlation (ie. score under some threshold value for mean or variance or best score not lying much higher than average score) need to be marked as ‘mismatched’ to prevent corrupting assesment of surrounding lines.

- PAL Phase detection & Finding Chroma phase difference: required if we want to decode color

- Edge detection: edges formed by left and right borders of the image are detected using a dynamic programming-based ‘edge detector’ which calculates the cheapest path from the top line down to any pixel based on the cheapest path to the pixels in the line above (with a path being ‘cheaper’ than another if it goes along a high-contrast edge and does not deviate much from a vertical line). Finding the correct edge representing image borders is difficult in images with many vertical lines running across the screen but due to the nature of the VideoCrypt scrambling algorithm cutpoints never appear nearer than a certain minimum distance (~12% of the image width) from the image borders. So edge detection has to avoid getting within range of the minimum distance thus excluding many false ‘alternative edges’.

- Cutpoint sequence discovery: Using dynamic programming we can combine the above information to find optimal cutpoint sequence for a given line assuming we have the one for the previous line. Mismatched lines are treated like the first line by giving each cutpoint the same score (the same happens when our restrictions on cutpoints yield an empty set)

- Cutpoint caching: Use a cache with lookup to prevent cutpoint candidate repetition

- Cut-and-Exchange: We cut the scrambled lines along our best cutpoint candidates and swap the line segments to yield our unscrambled image.

Demonstration

We can try out antisky on a videocrypt scrambled image provided on Kuhn’s website and effectively follow the ‘Anarchist’ manual procedure.

usr@machine:~# mogrify -format ppm r-vc1.jpg

usr@machine:~# gcc -lm -o antisky antisky.c

antisky.c: In function ‘main’:

antisky.c:615:5: warning: incompatible implicit declaration of built-in function ‘memcpy’ [enabled by default]

usr@machine:~# ./antisky -1 -r20 r-vc1.ppm r-vc1.decrypted.pgm

usr@machine:~# mogrify -format png r-vc1.decrypted.pgm

As noted in the training manual, the descrambling process is a bit of a ‘trial and error’ affair which involves stepping through the parameter (ignoring a certain number of columns on the screen left and/or right hand sides, border marking or not, interline cross-correlation only, etc.) until they yield a decent enough unscrambled image. Once the optimal parameters for a frame within a feed have been found i’d imagine these scale quite well to the rest of the feeds for the drone in question.

VideoDecrypt: Another unscrambling approach

William Steer discusses another approach to unscrambling VideoCrypt-scrambled feeds on his website. While Kuhn’s program worked on images obtained using standard PC video-capture cards and at arbitrary resolutions/scan rates, Steer’s approach was to achieve ‘perfect’ (ie. glitchless, properly coloured) decoded images by relying on some basic assumptions about the target system. Steer gives an example where common set-top-boxes sampled the video signal at 14MHz so that with 256 possible cutpoints per line and the fact that cutpoints don’t occur within a minimum distance (Steer estimates this to be ~15% of width) of the left/right edges of the image, one can determine that cutpoints all fall on 1/(7MHz) intervals (ie. even pixel boundaries). Steer’s algorithm starts by filtering out the PAL subcarrier and leaves luminance-only information, rotates each line by all possible cutpoints relative to the previous line and calculates a square difference for each of those with the best fit occuring (except in rare circumstances) at the correct step (plus or minus one). Now the chrominance component of the line is investigated since on alternate lines within a field (assuming no change of colour) the PAL coding is 180 degrees out of phase which enables the best fit to be narrowed down to precisely the right cutpoint. After working through all the scanlines and assuming the process was successful the result is a pixel-perfect image but with a ‘rolled’ distortion in the horizontal sense corresponding to the right/left boundary. The image is rolled accordingly and shifted leftwards by 8 pixels to get alignment perfect PAL phasing with the whole process described as taking only 4 seconds on a 233MHz PentiumII under Windows NT4 (hence being virtually instantaneous on modern PCs). After unscrambling the image is processed by Steer’s PalColour program for coloration.

Lessons learned?

The most obvious ‘lesson learned’ here is that analogue PayTV scrambling algorithms from the early 90s are unsuitable for drone feed ‘encryption’ today. Well, duh. What is more interesting, however, is that techniques designed to keep low-budget TV pirates at bay more than 20 years ago appear to still be relevant. While the information the article draws upon dates back to 2010 and the UAV COMSEC landscape (at least, for the more sophisticated UAV operators) might very well have drastically changed since then, the fact remains that unencrypted military drone footage was still being intercepted in 2009 and beyond so there’s that. As a Hacker News comment mentions the reason for usage of such a dated scheme might not be as completely ridiculous as it seems. The existence of, admittedly moldy and old, off-the-shelf hardware solutions looks pretty attractive given that stronger encryption schemes will require a digital link with error correction which is not trivial to retrofit to drone models already in production.

Another interesting element here is the fact that the ‘cryptanalysis’ of VideoCrypt scrambled signals draws upon signals processing thus effectively relying on statistical properties of plaintext information propagating through to the ‘ciphertext’, not unlike classical cryptanalysis techniques like frequency analysis. So what is quite puzzling here is why the ‘Anarchist’ program decided to simply go with an open-source tool from 1994 in tackling this problem rather than applying current advances in signals processing and combine them with either an optimized software implementation or even a dedicated hardware one which would probably allow for real-time stream unscrambling with modern hardware. Or at least the stepping through the parameter space could have been automated to some degree here. Perhaps the responsible analysts didn’t deem the information important enough to warrant the effort but on the other hand the effort is hardly a herculean one, its more along the lines of ‘weekend hobby project’ than ‘cutting edge contemporary cryptanalysis’. Investigation of how widespread such old-timey analogue TV feed scrambling solutions in contemporary sensitive systems are and writing an improved (and perhaps more modular, to accomodate similar but slightly different scheme) version of the AntiSky algorithm (along the lines of Niedermayer’s variant above) would make for quite an interesting project though. Whatever the reasons for GCHQ’s usage of AntiSky rather than a tailored solution, it goes to show that, save for the required signals interception equipment, intelligence collection of this kind is not limited to well-funded state actors with a deep understanding of cutting-edge technology.

samvartaka 02 February 2016